Silent University

The empowering potential of complementary currencies and alternative payment systems

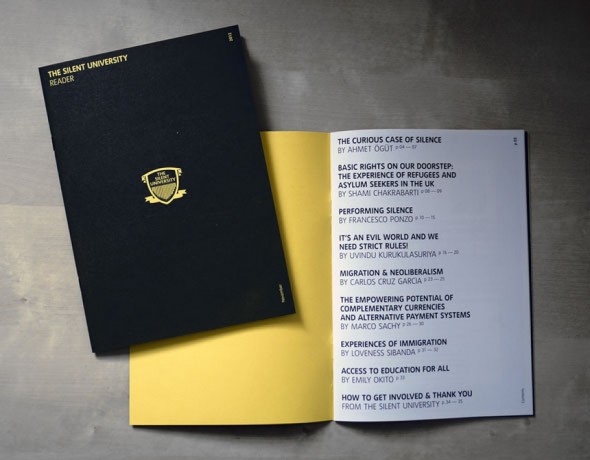

In the effort for building a better monetary system for everyone, DYNDY had the possibility to network with Tate and Delfina Foundations in the project The Silent University, hosted in a space inside Tate Modern gallery in London as “an autonomous knowledge exchange platform by and for refugees, asylum seekers and migrants”.

Led by a group of lecturers, consultants and research fellows, various groups have been contributing to the programme in different ways which include course development, specific research on key themes as well as personal reflections on what it means to be a refugee and asylum seeker.

Below is Marco Sachy‘s intervention on the issue of money, innovative technological developments for PSPs (Payment System Providers) and new desirable social and political landscapes designed around the needs of those who are not legally allowed to open a conventional bank account – since they do not officially exist within the borsers of one of the most advanced countries on the planet.

When it gets down to having to sue violence, then you are playing the system’s game.

– John Lennon

Global capital oppresses the individual in an all encompassing manner, which leaves little space for meaningful and active resistance. In every country of the world, the level of access to national currencies is nevertheless the parameter that most remarkably influences the condition that one experiences in modern society, i.e. the Freedom of Economic Interaction that one can enjoy. Borders to such freedom have been purposely designed by a handful of international financial institutions in conjunction with banking and non-banking corporations, which form a de facto ‘network of global corporate control’ operating at a transnational level with conniving States’ apparata for law enforcement. Indeed, a team of researchers at the Department of Systems Design at the University of Zurich published in late 2011 a paper in which they showed that each of the core 147 most powerful corporations worldwide owns shares of the remaining 146 composing such nucleus of power and have at their top the most important international and national financial institutions legally owning the system itself (Vitali, Glattfelder and Battiston, 2011). This, at the very outset, is the framework of the current institutionalized monetary system, whose features permeate the lives of each individual on the planet, either she is juridically assimilated within society or not.

After a historical analysis, one can notice that the system presents structural problems highlighted by the present global economic crisis, which is the last and biggest of a very long series dating back to the dawn of the modern monetary system in the seventeenth century (Kindleberger, 2005). Since 1970 only, the IMF identified 145 banking crises, 204 monetary collapses and 72 sovereign debt crises (Lietaer and Belgin, 2011). More at large, for the past three hundred years, society has been dealing with a centralized and privately owned monetary system explicitly designed to issue with full discretion and manage with almost total unaccountability a very particular type of money, i.e bank money (Hutchinson et al., 2002). Although the latter is usually identified as the ‘national currency’ of a country, the private issuance of 95% to 97% of a nation’s money supply by the commercial banking sector, i.e. the only currency for the payment of taxes, shows the migration of power towards private banking at the expenses of the public sector and society at large: “Governments have the right to exert power over their citizens and over the businesses active in their territory. Therefore, whoever can control governments can project power over the world.”(Lietaer, Anrspenger, et. al., 2012)

It is well that the people of the nation do not understand our banking and monetary system, for if they did, I believe there would be a revolution before tomorrow morning.

– Henry Ford

Modern bank money presents in turn a series of theoretical shortcomings, which define the socio-economic contract that every citizen of a State in entitled with – and is obliged to adhere to – in order to ‘freely’ live in such nation state: it is debt-based money, which has no intrinsic value in the current fiat money system. It is loaned out at interest to governments, businesses and private individuals, but the money necessary for the total repayment of the interest on the loan is not brought into existence as the loan is granted with the signature of the borrower. Further, although it is a considerably widespread means of exchange, modern bank money is not a reliable unit of account nor a safe and robust saving instrument (Douthwite, 1999). Finally, modern bank money is inflationary and its management follows a vertical hierarchic organizational structure of governance, which may trigger conflicts of interests by virtue of informational asymmetries. Accordingly, conventional money is a type of money legally enforced on the vast majority by a tiny minority: commercial and central banking institutions can increase the global level of debt, i.e. the money supply, with digits on a keyboard and the multiplier effect of fractional reserve practices while new loans are collateralized by real assets and future labor in an intergenerational ponzi scheme.

Those shortcomings are the blueprint for all conventional money, i.e. national currencies that almost everyone is familiar with. True, traditional monetary economic textbooks describe money in instrumental terms (unit of account, means of exchange, store of value), either intentionally or unwittingly or still unconsciously, and such widespread functional definition contributed through time to hide the nature of money from the majority of academics, users and providers. As John K. Galbraith summarized the background on this issue: “The study of money, above all fields in economics, is the one in which complexity is used to disguise truth, or evade truth, or not to reveal it.” (Galbraith, 1975) Thus, why is it so important to acknowledge the nature of money and distinguish it from what money does? Only in this way, it is possible to be aware that, although it enjoys a complete monopoly in the form of a banking cartel, modern bank money is only one type of money among many possible ones, a peculiar kind of software for social behavior so to say, which establishes the specific kind of social contract sketched above. But what is money then? At the ontological level, money is simply an agreement within a community to use something as a means of payment (Lietaer, 2001). In particular, the ontology of money is relational, abstract and cogent as agreements in general are and the possibilities to formulate the agreement are unimaginable, if one bears in mind that the the orthodox process of currency design and creation is – by drawing from Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of the Enlightenment – an arbitrary and historically determined one (Adorno and Horkheimer, 1947).

Contrary to modern bank money, Complementary Currencies (CC) and Alternative Payment Systems (APS) may be intentionally designed not to carry the burdens affecting commercial bank money and to potentially eradicate them. In fact, CCs and APSs can be designed to improve and perfect the monetary system, and to fill such holes that modern bank money is designed to leave empty is only the first step toward a a multi-currency system where a diversity of moneys will posses legal tender power. In turn, it is knowledge or, better, the empowering effect of monetary knowledge must therefore become widespread among the members of society in order to make the state of recurrent crises of a top-down system a weird practice of past ancestors. In other words, an alternative naturalization of money will be as arbitrary as previous ones, but it will also perform potentially better in that it will derive from a more conscious cognizance of cause, i.e. an ontological one. This reflects already in the thousands of CCs and APSs that have been operating worldwide during the past decades[1]. Indeed, by matching unused resources with unmet needs, CCs substantiate APSs, which graft on the currently collapsing system by counteracting the shortcomings of conventional money. They are used in parallel with – as complements to – national currencies thanks to design strategies such as zero interest or negative interest rates, real-asset backing (intrinsic value), decentralized issuance (e.g. mutual credit systems), transparent management and public auditing, etc.

…the most effective way to counteract the violent socio-psycho-pathological dynamics of financial capital is to weaponize money…

Thusly, at these first stages of social monetary emancipation in the 21st century, either those within the system who are aware of the nature of the agreement framed by conventional money or those who are financially and juridically excluded, better together, can organize spaces of effective monetary resistance. Rather than riots in the streets, by paraphrasing Marazzi (Marazzi, 2010), the most effective way to counteract the violent socio-psycho-pathological dynamics of financial capital is by developing a sort of weaponization of money as the most effective non-violent strategy to adopt at present. Indeed, solutions are emerging from within the system itself in terms of campaigns for endogenous monetary reform (e.g. in the UK, ‘Move Your Money‘ and ‘Positive Money’ campaigns), new theoretical developments such as those by the representatives of Modern Monetary Theory (Brown 2008) and the Neo-Chartalist School (Wray, 1998), new forms of pooling (e.g. the JAK Bank in Sweden) and direct credit clearing (Greco 2009). However, there are also valuable alternatives that are exogenous in character and therefore suffer less from the inherent flaws affecting conventional money:

- LETS (Local Exchange Trading Schemes mostly in the US and UK) and LOVE (Local Value Exchange in Japan).

- Transition currencies, e.g. Transition Pounds in the UK, mainly as local loyalty currencies for shielding and insulating the local economy from external financial perturbations (North, 2010).

- Business-to-business currencies, e.g. C3 or Commercial Credit Circuit in Uruguay, whereby businesses use invoices as a currency to sustain the SMEs sector.

- Developmental currencies, e.g the Palma, a currency designed in Fortaleza (Brazil) that by endorsing the principles of Solidarity Economics (Miller, 2004).

- Social Purpose currencies, e.g. the Fureai Kippu a currency for the elderly care widespread in Japan or the Chiemgauer, a regional currency issued in Bavaria (Germany) to sustain local businesses and local charities in the same scheme.

As for every list and for obvious reasons of space, the above is only meant to give a flavor of the diversity of applications that currency design is capable to offer.

Further, from the cyberspace, there will probably come technological innovations that will enable a further detachment from the yoke of the conventional system through increasing dis-intermediation or this, at least, is a reasonable way to interpret the words of the Governor of the Bank of England, Sir. Mervin King as for 1999: “the successors of Bill Gates would have put the successors of Alan Greenspan out of business.”[2] Indeed, the shift is now steadily underway in prototypical forms of digital born currencies, e.g. Bitcoin (Nakamoto, 2009).

It is not hard to imagine in effect a future where transfers of money among actors in the economy will proceed in real time and horizontally, similarly to what happened in the switch from paper mail and email. Banks – as post offices before them – will not close, they will just experience a reduction in their preeminence in the process of exchange of money, with desirable advantages for the users of a monetary system charging very low transaction costs. A technology such as Bitcoin has indeed extremely interesting applications: for instance, the possibility to link at the monetary level individuals living far from their homeland such as either legal or illegal immigrants to send money, for example remittances, to individuals in their home country. As a desirable result, a widespread use of the Bitcoin technology could put in danger the oligopoly of wire transfer companies that currently demand very dear commissions and fees for settling accounts (e.g. Western Union or MoneyGram). Another interesting feature of the Bitcoin technology is the possibility to transfer money under pseudonymity and, in extreme cases, anonymity. This could make a crucial difference in protecting the lives of political refugees and asylum seekers worldwide who can now transact with a safety never experienced before. True, in the recent past, as Master Card, VISA and Pay Pal temporarily interrupted the stream of donations, Wikileaks has experienced Bitcoins – redeemable like precious metals in either US dollars, Euros, or still Pound Sterling – as the only source of funding[3].

In conclusion, as feminism arose for the sexual emancipation of women the XX century for bringing a cultural end to the taboo of sex in Western societies, in the beginning of the new century the movement for alternative currencies is rising for the abolition of another taboo, the taboo around money. However, alternative currencies will not be enough if a just economic system and society is to obtain. In effect, the potential success of the alternative currency movement would be only the first step towards reverse engineering the conventional system in order to invert the process of subsumption of society into capital into a process whereby the money system is driven from democratically controlled priorities (Negri, 2002; Mellor, 2010). Hence, to dare a reversion of the current operational organization of the conventional monetary system is priceless, its impact would be positively incommensurable at the socio-economic level, but the value of a concrete attempt – pace Henry Ford – still remains infinite.

Footnotes

[2] The Guardian, 27th August 1999 (retrieved at http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/1999/aug/27/14 on 12th October 2012).

[3] Denis “Jaromil” Roio, Bitcoin2012 Conference, London, speech held on 15th Sep. 2012.

References:

– Adorno, Theodor W. and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of the Enlightenment – Philosophical Fragments, edited by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr and translated by Edmund Jephcott. Stanford University Press: Stanford, 1947 /[2002].

– Brown, Ellen, Web of Debt: The Shocking Truth About Our Money System and How We Can Break Free, Third Millennium Press, 2012.

– Douthwaite, Richard, The Ecology of Money, Schumacher Briefings (No 4). 1999.

– Galbraith, John K., Money: Whence it Came, Where it Went, Boston: Houghton Muffin Co., 1975.

– Greco, Thomas H., The End of Money and the Future of Civilization, Chelsea Green Publishing, 2009.

– Hutchinson, Frances, Mary Mellor and Wendy Olsen, The Politics of Money – Towards Sustainability and Economic Democracy, Pluto Press: London. 2002.

– Kindleberger, Charles P., Manias, Panics, and Crashes – A History of Financial Crises, Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. 1978 (5th ed., 2005).

– Lietaer, Bernard, The Future of Money, London-NY: Randomhouse. 2001.

– Lietaer, Bernard, and Stephen Belgin, New Money for a New World, Qiterra Press, 2011.

– Lietaer, Bernard, Christian Arnspenger et al., Money and Sustainability – the missing link, Triarchy Press, 2012.

– Marazzi, Christian, The Violence of Financial Capitalism, Semiotexte, 2010.

– Mellor, Mary, The Future of oney: from Financial Crisis to Public Resource, Pluto Press 2012.

– Nakamoto, Satoshi, Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System (retrieved at http://goo.gl/RdYQO on 23 May, 2012), 2009.

– Negri, Antonio (Foreword), Andrea Fumagalli, Christian Marazzi, and Adelino Zanini, La Moneta nell’Impero (Money in the Empire), Ombre Corte, 2002.

– North, Peter, Local Money – How to Make It Happen in Your Community, Transition Books, an imprint of Green Books. 2010.

– Vitali S., Glattfelder J.B., Battiston S., The Network of Global Corporate Control”. PLoS ONE 6(10): e25995. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025995 (2011).

– Wray, L. Randall, Understanding Mondern Money: the Key to Full Employment and Price Stability, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. 1998.